My trip began in earnest when I left Portland, Maine for Anchorage, where

I met AAI's guides and the rest of the team. Arriving late at night, I was greeted by another team member at the airport;

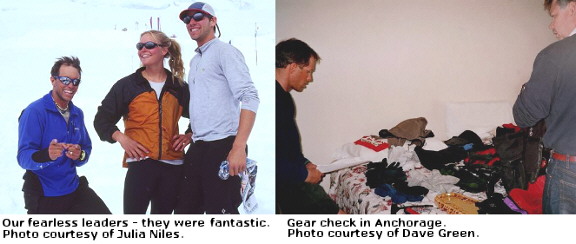

we shared a cab and hotel room. After a foot tour of Anchorage the next morning, he and I met the group. Our guides were John

Kear, Julia Niles and Seth Hobby, each exceptionally fit and skilled after years of guiding and climbing in the Cascades,

Rockies, Andes, Himalaya and Alps. The rest of our team was also very strong and experienced; everyone had climbed high peaks

in the Andes, Cascades or Sierra Nevada, and one had climbed previously on McKinley. There were two fairly distinct age groups:

those in their early to mid-twenties, and those in their late thirties or older, with the oldest member in his early 50s.

The team included a physician, two lawyers, an engineer, an architect, an air traffic controller and two graduate students.

Two of the clients were Canadian, two British and the rest American. In addition to Julia the guide, there was one other woman

on our team. Although diverse, we proved to be very compatible and cohesive.

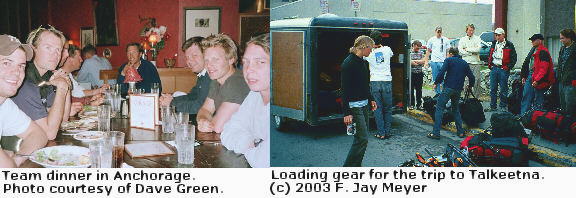

At the hotel in Anchorage our guides gave us a briefing on the route, then

performed a thorough inspection of each client's equipment. Anyone who needed or wanted additional gear had time to

visit several Anchorage outdoor stores. That night we became better acquainted over dinner at a downtown restaurant.

The next morning we woke up early and loaded a big shuttle van and trailer

for the trip north to Talkeetna. This town, an important transportation center for Denali National Park, mixes quirky northwoods authenticity with the trappings of tourism. At

Talkeetna's airport we arranged our gear for the flight to base camp. The climbers and gear were weighed to prevent

overloading. We were fortunate that the weather was suitable for flying that day; many climbers have endured long waits

in Talkeetna when conditions were unsafe for glacier landings. But climbing season was in full swing when we arrived,

and there was a backlog of teams checking in with the National Park Service. So while we waited our turn to register and then fly, we explored town and

made last minute phone calls.

After meeting with the Rangers we returned to the airport, where we loaded into two ski planes. Cessna

185s are ubiquitous in Alaska, but K2 Aviation's larger DeHavillands were more suitable for our twelve member expedition. Four of the team left first in

a radial engined Beaver; the others and I then loaded into an impressive, turbine powered Otter. Although carefully

weighed and organized, our gear was bulky so the boarding process was more like a mosh pit than a major airline!

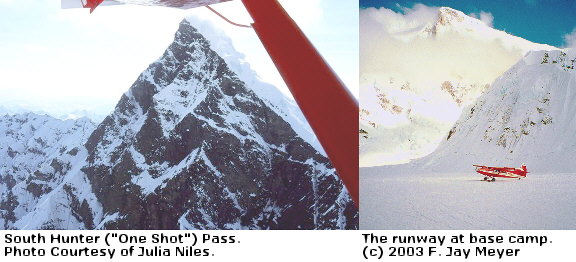

The flight north over the marshy subarctic taiga to the glaciers and crags of the central Alaska Range was spectacular.

The threshold between the foothills and giants of the interior is South Hunter (or "One Shot") Pass - a V shaped notch

in Mount Hunter's flank that heavily loaded ski planes can often, but not always, squeeze over and through. Sadly, two

climbers, a sightseer and a pilot died when their plane crashed in this same pass only days after our flight. But we

flew in without incident and forty minutes or so after we lifted off, the big Otter settled onto the packed snow runway at

base camp.

|