|

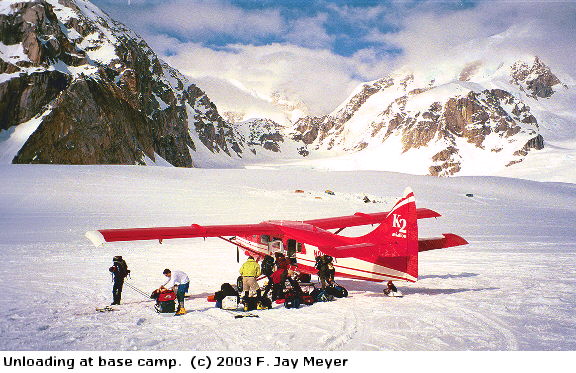

As soon as the Otter slowed to a halt, we piled out and unloaded our gear. The team members who arrived earlier in the

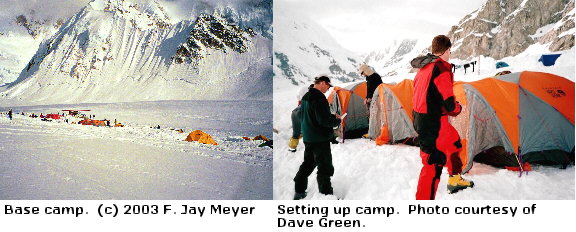

Beaver had already selected a spot and pitched several tents in base camp, which lies next to the snow runway. The rest

of us finished the job of setting up our first camp, leveling tentsites and digging a large pit for the kitchen tent. This

would be the first of many nights camping together, and the relatively benign environment of base camp provided a good opportunity

to sort out our camp routine and group gear.

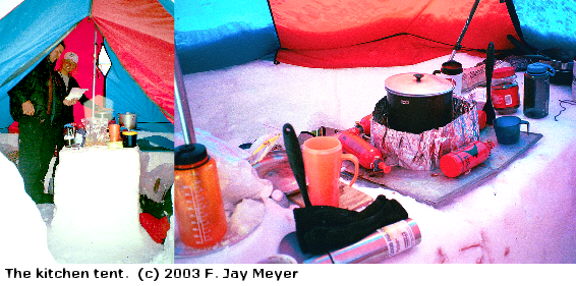

Our camp procedures were fairly uniform throughout the trip, except at high camp where we spent nearly all of our time in

sleeping bags sheltering from the cold and wind. In the lower camps we ate and socialized in a large kitchen tent pitched

over a snow pit with seating around the perimeter and a central counter for stoves and cookware. The guides cooked,

and particularly on the lower mountain we had an ample quantity and variety of food. Our fare included pasta, beans,

rice, bagels, cheese, canned meat, fish and vegetables, dried fruit, nuts, hot drinks such as cocoa and tea, and a plethora

of nutritional bars. All of our water was melted from snow using white gas stoves, a process performed regularly whenever

we were in camp. In our smaller tents we read, talked, wrote in journals, listened to the radio, slept or just stared

at the walls.

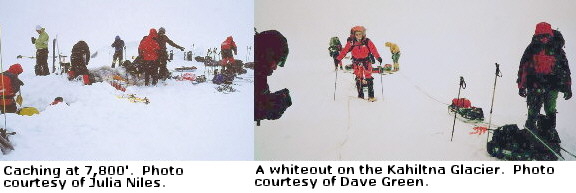

The morning after our arrival, we began our move up the route. On the glacier we carried gear and supplies in backpacks

and sleds, allowing us to move heavy loads. But with so much food and fuel for our long trip, it was impractical to carry

everything in a single push; instead, we alternated carries, where we moved supplies and buried them in a cache, with camp

moves where we broke down our tents, kitchen, etc. The first morning we carried loads to cache at a future campsite. After

rigging up our sleds we headed down the Southeast Fork and onto the main branch of the Kahiltna. It was cold and, at first,

snowing lightly. But soon the snow fell heavier and blew into blizzard. We used snowshoes as any semblance of a trail quickly

disappeared. In whiteout conditions the guides used GPS to find our way to the cache site, approximately five miles from base

camp. There, in the blowing snow we dug a deep pit and buried our load of food and fuel. The return to base camp was difficult;

we lost our way several times on the foggy, crevasse strewn glacier, finally snaking back to base camp almost twelve hours

after we began.

Overnight it snowed heavily, and in the morning we knew that we would not be moving that day. Instead we shoveled snow,

ate and rested. But the next day the weather was clear and we got a cold, early start for our move to the campsite where we

had cached two days earlier. We got to that site around noon and began the process of leveling tentsites, building snow walls

for wind protection and digging a pit for the kitchen tent. Then we had some time to laze in the warm afternoon sun. The next

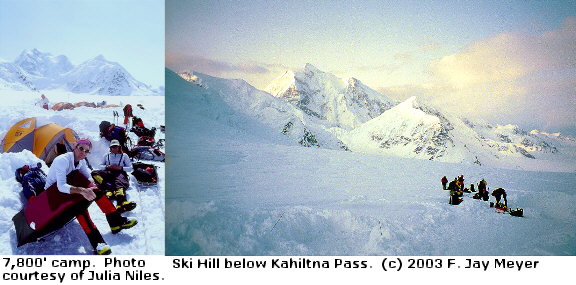

morning we carried a load up Ski Hill's long slope to Kahiltna Pass (approximately 10,000'/3,050') where we cached, admired

the view down the Kahiltna, then returned to the 7,800'/2,400 m. camp for another night.

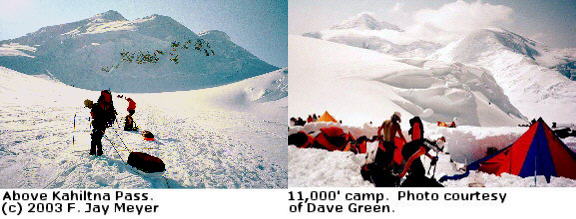

The following day we moved up, past our cache at Kahiltna Pass, to a third camp at 11,000'/3,300 m. This was a popular

campsite where many teams waited out bad weather and prepared to move higher, up steep slopes and past aptly named Windy Corner

to the top of the Kahiltna. With our heavy loads we were starting to feel the altitude, but almost immediately after arriving

we dug into the task of constructing large protective snow walls for our tents. Though this campsite could be pleasantly

warm during the day in sunny weather, it could also be very cold at night or when the weather turned. The day after arriving

there we retrieved our cached supplies from Kahiltna Pass, and the next day we waited out a windy snowstorm.

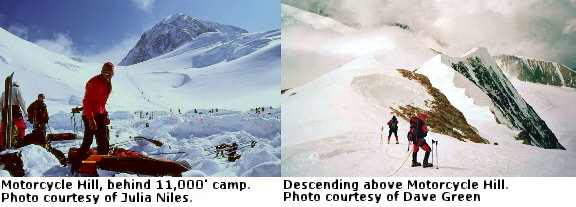

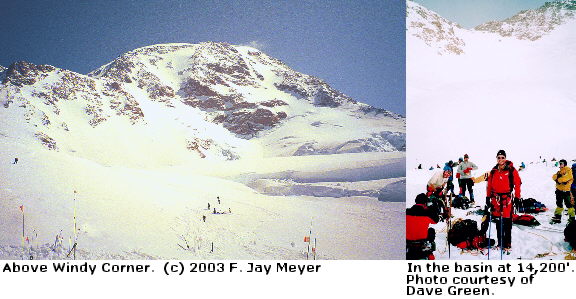

After two and a half days at 11,000'/3,300 m. we were restless to climb higher. Above that camp, the route first ascends

Motorcycle Hill, then continues up open windblown slopes and around a shoulder of the West Buttress - Windy Corner - that

is often impassable in bad weather. From there to the basin at 14,200'/4,300 m. lies a region of huge crevasses formed by

the glacier's wrenching turn around Windy Corner. Our first trip past Windy Corner was to carry supplies for caching in the

basin. We used sleds, but they were becoming clumsy on the steeper, icy slopes. It was cold and the wind bit as we made an

early start, but we quickly warmed when the sun rose higher. Past Windy Corner, after a long break to catch our breath, we

pressed on and made our cache at 14,200'/ 4,300 m. During lunch in the basin we got our first good view of the West Buttress'

ridge and headwall, then descended back to 11,000'/3,300 m., stopping on the way to look out over the Peters Glacier. The

next day we broke camp at 11,000'/3,300 m. and moved to 14,200'/4,300 m., leaving behind a large cache of waste and items

such as snowshoes that would not be needed until we came back down the route.

|