|

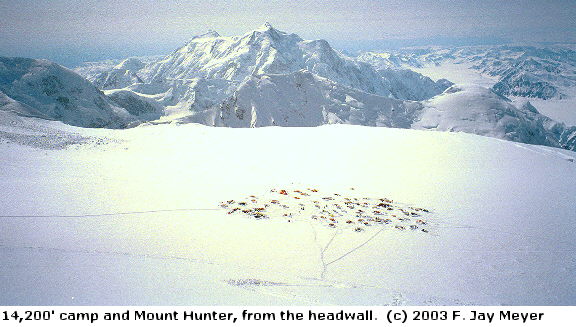

At 14,200'/4,300', in the basin at the top of the Kahiltna, is perhaps the most important campsite on the West Buttress

route. During the climbing season National Park Service Climbing Rangers maintain a constant presence there, with radios

and basic medical equipment. Several routes other than the West Buttress, including West Rib variations and the Messner

Couloir, lead through this camp. We were there at the height of the season, and the camp was crowded with more than

a hundred climbers of many nationalities.

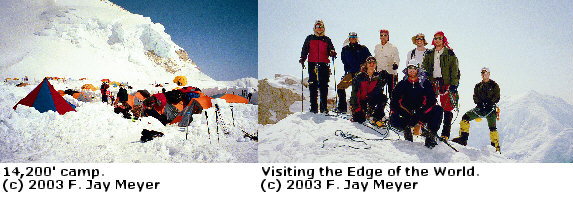

After arriving we spent hours preparing our tentsites, kitchen and protective snow walls. This ritual became more difficult

as we climbed higher, with harder snow and thinner air. The next day was planned as a rest day, but in fact we were quite

busy. In the morning three of us climbed part way up the headwall to get a better look at the fixed ropes and picturesque

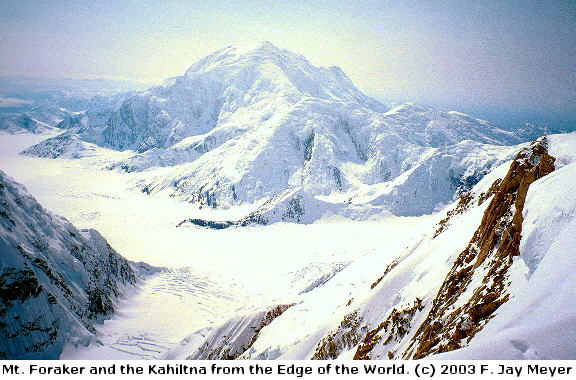

surroundings. Two of the guides climbed a mix of snow and rock to the ridge of the West Buttress. Later most of us walked

to the "Edge of the World" at the basin's outer lip, where we had views of several Denali ridges, Mount Foraker, Mount Hunter

and the sweep of the Kahiltna below. Back in camp we practiced techniques such as running belays and ascending a fixed line,

to prepare for the climbing that lay ahead.

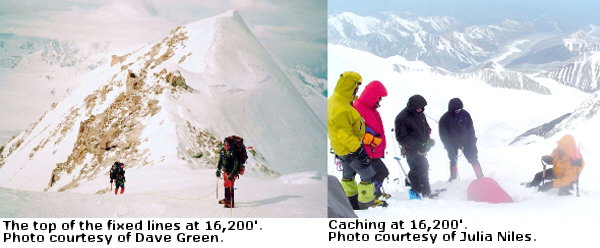

We had a chance to use some of those techniques the next morning, when we carried supplies up the steep headwall to the

top of the fixed lines (approx. 16,000'/4,900 m.). There we cached our supplies in hard snow, and took a closer look at the

rocky ridge leading to high camp. Then, in a sudden cold squall we hastened back down the headwall to the basin camp.

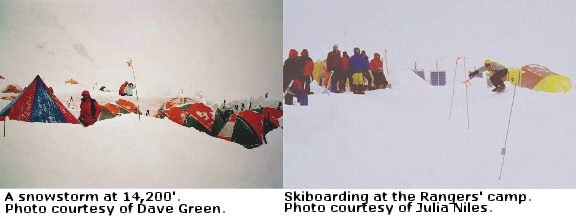

We had hoped to climb all the way up the headwall and ridge to high camp the next day, but that plan was foiled by bad

weather. We actually spent the next two days stormed in at the basin camp. Several feet of snow fell, and we could hear booming

avalanches on slopes all around us. Again we settled into a routine of shoveling, eating, reading and napping. To break up

hours in the tent, I walked around camp in the blowing snow. All of the other teams were in a similar predicament, unable

to move higher due to the weather. The second day, many bored climbers flocked to the Rangers' tents for an impromptu skiing

and sliding exhibition on a handcrafted course.

After two stormy days the weather cleared, and most of our team prepared for the climb to high camp. One member decided

that he was happy with the trip to that point, but ready to return home; the guides arranged for him to join another team

on its descent to base camp. We then struck camp, leaving the kitchen tent and other heavy or superfluous items. Many

teams were moving up in this same weather window, and a line quickly grew on the slope below the fixed lines. The leading

teams were assessing avalanche hazards, and everyone behind them waited in the deep new snow. Finally the teams surged

upward, but then clumped together in a bottleneck at the base of the fixed lines. The process was slow as each climber

clipped onto a rope and ascended in single file up a path of steps kicked into the steep hard face.

When our team's turn came, we moved quickly up the fixed lines despite our heavy loads. At the top of the lines we gathered

where we had cached three days earlier. One member had suffered breathing problems on the headwall, and decided to return

to the basin camp with a guide. The rest of us split up most of the cached supplies and loaded them into our already bulging

packs. We left some supplies cached, on the chance that we might need them if we spent more than a few days at high camp.

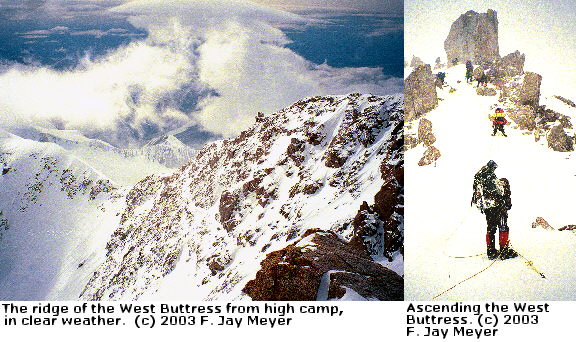

Unfortunately, the weather had deteriorated while we were climbing the headwall. On the ridge the force of the wind

caught us, the temperature dropped, and the visibility rapidly worsened in blowing snow. This portion of the route is

well known for its challenging terrain; in spots the ridge is sharp and exposed, and it is punctuated by huge granite boulders

scattered among patches of steep icy snow. We headed up into the storm, alternately moving and then waiting as others

ahead of us negotiated difficult sections of the route. Several times we huddled in the cold, considering the possibility

that we might need to turn around if we could not move more quickly up the crowded route. Some teams did turn back,

while others dug precarious camps on the ridge or hunkered in an old ice cave. But we were able to advance, and as we

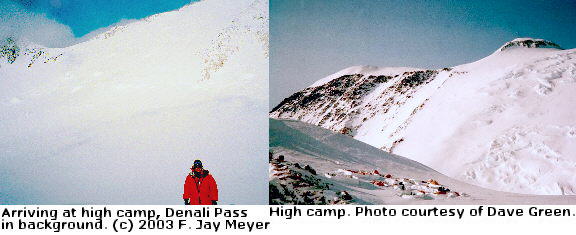

rose higher the route eased and the snow finally settled out of the stiff wind. Twelve hours after we left the basin

camp, we labored over the final knob of the ridge and then down a short slope into high camp at 17,200'/5,250 m. After

a short break to catch our breath in the thin cold air, we spent hours building camp walls with blocks of hard sawn snow.

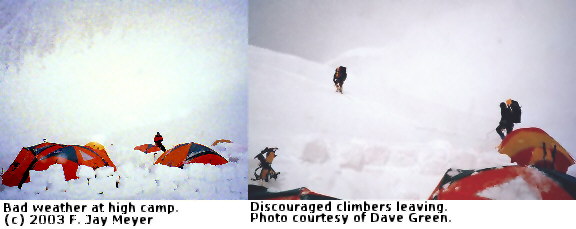

We hoped to stay only two or perhaps three nights at this camp, but in the end we spent five. For the first three days

we endured the whims of the weather. Aside from a few short walks to visit neighboring camps or enjoy the views from atop

nearby Rescue Gully, we were tentbound. We had carried up only the bare necessities, and so dispensed with many creature comforts. Cooking

was limited to melting snow and adding the heated water to dried food, which the guides did in their tent vestibule. Because

we had limited time and supplies, each passing day was an emotional rollercoaster. We listened to weather forecasts and hoped that the next day would be calm enough for a summit attempt, but entertained the possibility that we might descend

without ever having a chance to reach the top. One day, three Russian climbers headed for the summit through high wind and

blowing snow; we heard that one turned back, but two toughed it out and made it the whole way. Another day a guided team climbed

slowly up toward Denali Pass, pausing frequently to dig avalanche pits in the fresh snow, but turned around at the pass due

to high winds. Aside from them, the climbers at high camp waited, watched and hoped.

When it became clear that we would be spending more than a couple of days at high camp, a guide descended to our cache

at the top of the headwall to retrieve more food and fuel. But our supplies were still limited, and we were swiftly approaching

the date when we had to fly off the mountain and return home. We arrived at high camp on Sunday, June 8, and by Wednesday

some other teams began descending, abandoning their summit hopes. One member of our team had a crucial work commitment, and

to assure a timely return he descended with a guide on Wednesday morning. In fact, we all considered descending on Wednesday,

but remained in the hope that it might clear on Thursday, the last possible day for us to attempt the summit. On Wednesday

evening we heard a forecast for improved weather the next day. But we knew that even if we did reach the summit, our schedule

would then necessitate a grueling, continuous descent from high camp all the way back to base camp if we were to fly out on

time.

|