|

|

|

|

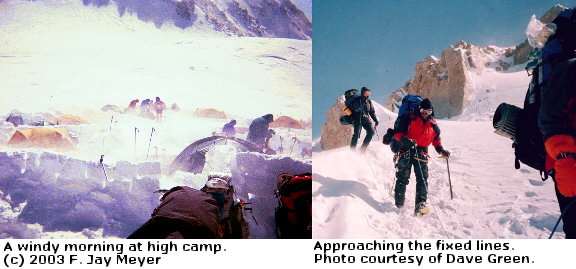

Exhausted, we retired to our sleeping bags shortly after returning from the summit. Overnight the wind kicked up

again, and we were glad to have reached the top in such a small window of good weather! It was only too easy to sleep a bit

late in the morning, but we had a long way to travel so by mid-morning we began to break camp. Around 11:00 a.m., with our

packs heavily loaded, we started the tricky descent of the West Buttress' ridge. Although it was windy and cold, the weather

was clear so we had beautiful views of the Peters and Kahiltna Glaciers. We reached the fixed lines at the top of the headwall,

descended them, and by early afternoon were back in the basin camp. There we met another American Alpine Institute team and

spent a couple of hours with them, snacking and sharing our experiences at high camp and on summit day.

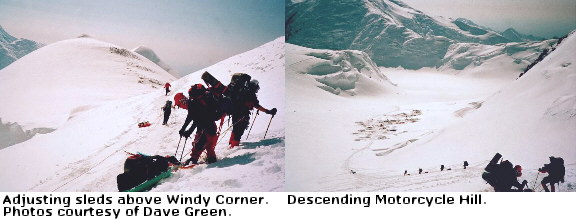

When we had departed the basin camp for high camp five days earlier, we left a large cache of gear and trash; we now

needed to bring it all down with us. Fortunately we had also cached our sleds to help carry the extra load, but they would

prove a mixed blessing on the steeper portions of the descent. After digging up and loading the cached items into our packs

and sleds, we departed the basin camp to descend around Windy Corner. The mid-afternoon sun kept us very warm as we carried

our heavy burdens. Crossing or descending steep slopes our sleds were difficult to control, lurching forward, swinging sideways

or tipping over. We experimented with different methods of rigging them, but none worked very well.

Below Windy Corner, we descended Motorcycle Hill and reached the 11,000'/3,300 m. camp at its base. There we stopped

to recover more cached gear and trash, then resumed our descent. With the additional load our sleds become even heavier and

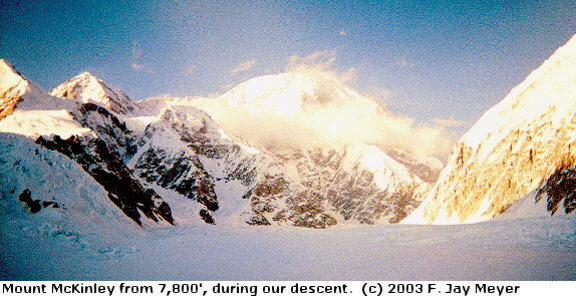

harder to manage; we struggled with them repeatedly above Kahiltna Pass and on Ski Hill. At the base of Ski Hill

we stopped near the site of our second camp (7,800'/2,400 m.), and took a long break to rest and eat. We considered

camping at this site and then getting an early start back to base camp the next morning, but by this time the "smell of the

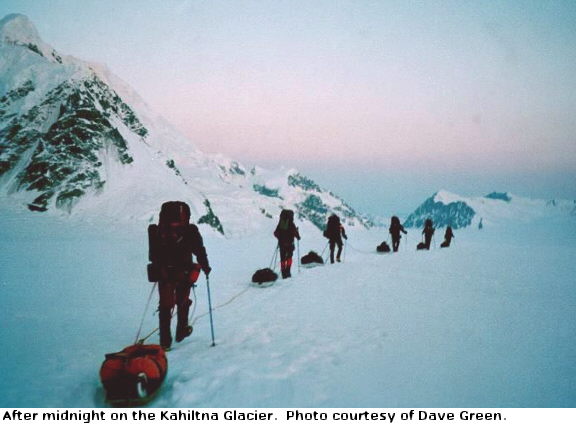

barn" was a strong lure and we decided to continue onward. It was nearly midnight, but in mid-June at this latitude it

is light around the clock and we had no problem navigating across miles of crevasse strewn glacier to the base of the Kahiltna's

Southeast Fork. There we made one final ascent up Heartbreak Hill and, around 2 a.m., arrived back in base camp. In fifteen

hours we had descended all the way from high camp to base camp, a distance that we had taken fifteen days to ascend.

Because we hoped to stay at base camp for only a few hours before flying out in the morning, we did not spend time setting

up camp. I slept on a mat in my insulated parka and overpants, not bothering to use my sleeping bag. As it turned out this

was fortunate, because around 7 a.m. the guides came around to rouse us for a plane that was scheduled to arrive in less than

an hour. We hurriedly collected and moved our gear to the side of the packed snow runway, ready for loading onto the plane.

Right on schedule the big DeHavilland Otter appeared, flew a turn around base camp and then landed. We wasted little

time loading our mountain of gear and refuse into the plane. I was offered the chance to sit in the co-pilot's seat, an opportunity

that I readily accepted! Shortly we were airborne, and by mid-morning we were on the tarmac in Talkeetna, our gateway back

into civilization.

Returning to Talkeetna we experienced a jarring culture shock. After weeks on the mountain and glacier, surrounded by

snow, rock and other climbers, we were now in a town full of cars, tourists, businesses, trees and greenery. After

we unloaded the plane, I talked my way into a shower at the airport's tourist information building. It was unmitigated pleasure to

peel off clothes that I had been wearing for many days, and then soak off the accumulated grime and perspiration. After changing

into a pair of jeans, a clean shirt and comfortable shoes, I felt like a different person.

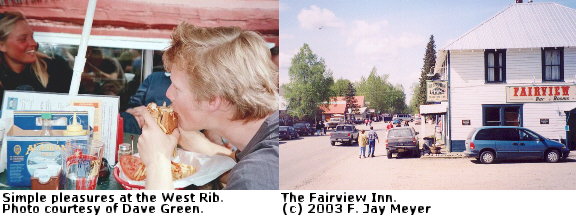

We then rode over to a local motel, and while others took showers I made some phone calls to let loved ones

know that I was back and safe. Then, we met at the West Rib for hearty food and uncounted rounds of strong Ice Axe Ale. After

lunch the events of the last few days caught up with us, and many returned to their rooms for a nap. That night we collected

for a celebratory dinner, then retired to the notorious Fairview Inn for toasts and casual conversation. It was fascinating for us to compare notes with other climbers who were back in Talkeetna

after their expeditions, many having summited on June 12 as we did.

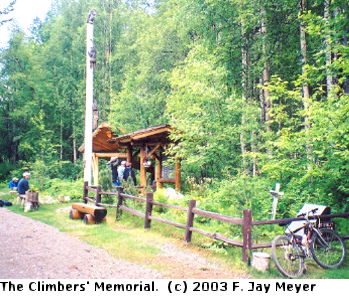

Almost as soon as we were back in Talkeetna, team members began saying their farewells and leaving for the trip home.

Before departing Talkeetna, my tentmate and I visited the Climber's Memorial in the town cemetery, an inspiring remembrance

of the many climbers who did not return from their expeditions in the Alaska Range. With several other members of our team,

I traveled back to Anchorage on Sunday, June 15, and from there we went our separate ways. I flew back from Anchorage on June

16 and, after several connections, arrived home the next day.

As I write this, it has now been five months since I returned from the summit of Mount McKinley. Has this experience

changed me, and what meaning can be drawn from it? I returned a little thinner and a little hairier, but with the exception

of two bruised toes I suffered no injuries. I attribute my success and well being to diligent preparation, skilled guides,

a worthy team and a healthy dose of good luck. But on a deeper level, achieving this great goal has proved to me that dreams

can be made real through hard work and patience. And at the same time it has caused me to reassess my goals, because if one

believes that dreams can come true, then it is even more important to consider which dreams to pursue.

|

|

|

|

(c) F. Jay Meyer 2007 All Rights Reserved

|

|

|

|